“GOD, COUNTRY, KING!” Moroccan national motto, but where have I heard that before?

I’ve not long returned from a couple of weeks touring around Morocco; my first visit to the country. It is a hugely varied country that impressed me in many ways but depressed me in a couple of other ways; most especially in the way both religion and monarchy are so conspicuous just about everywhere you go.

This indoctrination is woven into the very fabric of everyday life. The day begins with the obscenely loud calls to prayer broadcast from every minaret well before dawn breaks. Rarely did I find myself completely out of earshot of these intrusions, and on one occasion I found myself sleeping virtually next to a mosque and was rudely awoken at 6.30 am as if by someone standing next to my bed with a loudhailer on full volume! There must be cardiac arrests induced by this practice.

These calls to prayer are repeated 5 times a day in total, but I have to say that I only once or twice saw anyone even pause for a moment at the wailings during the woken day. They are like water off a duck’s back, washing over people virtually as if they didn’t exist. But the subliminal messaging is never missed. More on this later.

As for the monarchy, King Mohammed VI, the current monarch, seems to be held in pretty high esteem by most people, and his photo adorns the reception of every hotel, and is found in many business premises. His powers and role are very different to the monarch here. More on this later too.

The church and monarchy work closely together at times, as manifested in the previous king’s involvement at every stage in the creation of the truly magnificent, eponymously named, Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca. Completed in 1993, at a cost of something in the region of £500m, it was the biggest in Africa, with the world’s tallest minaret, until one in Algiers usurped both titles in 2019. But arguably the most impressive thing about it is that it was crafted almost entirely from Moroccan materials and by an army of Moroccan craftsmen. Quite staggering self-indulgence, befitting of both church and monarch.

Thus, the Moroccan people (subjects of the kingdom, but of varied origin and ethnicity – more on this later too) are unable to avoid the daily reminders of their position in Moroccan society. Even if you escape the cities, the authorities have adorned prominent hillsides along all major routes (and many less-major ones too) with the simple three-word motto: God, Country, King!

But hey, this is hardly original! Countries have been invoking the fear of God, ethnic nationalism and subservience to privileged elites since the dawn of civilisation!

Take the British, for example.

Since 1745 we have had to endure God, country and monarch rolled into one as the national anthem, ‘God Save the King/Queen’, extolling, without any evidence, the monarch’s graciousness, nobility, wishing them glorious victory in whatever. And that’s just the first verse:

God save our gracious King,

Long live our noble King,

God save the King!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us,

God save the King!

Thankfully we are usually spared the remaining four verses full of jingoistic incantations for God to send our enemies into disarray, in verse 2:

O Lord our God arise,

Scatter our enemies,

And make them fall!

Confound their politics,

Frustrate their knavish tricks,

On Thee our hopes we fix,

God save us all!

Verse three sounds a bit more peaceable, until you get to the end where it is clearly looking at global domination for the British Empire:

Not in this land alone,

But be God’s mercies known,

From shore to shore!

Lord make the nations see,

That men should brothers be,

And form one family,

The wide world o’er.

Verse four is about seeking divine protection for our noble, gracious King who somehow might pick up some enemies and potential assassins along the way:

From every latent foe,

From the assassin’s blow,

God save the King!

O’er his thine arm extend,

For Britain’s sake defend,

Our father, prince, and friend,

God save the King!

The final verse is the second most used verse, presumably because it is less offensive and merely cringeworthy, about showering the monarch with riches, and giving us cause to sing his praises, literally:

Thy choicest gifts in store,

On him be pleased to pour,

Long may he reign!

May he defend our laws,

And ever give us cause,

To sing with heart and voice,

God save the King!

No wonder this anthem consistently gets listed as one of the worst on the planet. Not that the Welsh anthem (Land of my Fathers) , the Scottish anthem (Flower of Scotland) or the English anthem (Jerusalem) are that much better. They are full of tales of laying down your life to defend the land, but they do at least cut out references to monarchs and have good tunes!

“God, King and Country” was the motto under which the British Army conscripts were marched off to be slaughtered in 1914 in that squabble between gracious nobilities seeking glorious victory over each other that evolved into “The Great War”. I rather hope that we are a bit smarter than that today. I would like to think such a motto as a clarion call to war would now provoke contention rather than unity.

If God were invoked at all, whose god or gods exactly? Have we established the existence of any of them? I would want to know! As for Kings, well, I think we have come to understand just how little the Windsors are worth dying for, being a dysfunctional rabble of little relevance to anyone. The king of Morocco seems to justify a little more respect, but enough to die for? And how relevant is our country in an increasingly global and interdependent world? Surely the demand “to die for one’s country” has lost its appeal, especially in Europe.

This is the essence of nationalism; even where borders are contrived, we are supposed to unite to fight allcomers and repel invaders/illegal immigrants, unless we can cherry-pick them, of course.

God, king, country; meh! You won’t catch me taking up arms to defend any of these concepts. Let me examine them each in a bit more detail, with UK and Morocco as exemplars.

COUNTRY

As hinted at above, both Morocco and the UK are contrivances. Virtually all current states are to some degree.

Those that know me will be familiar with my campaigning work, via Yes Cymru principally, in seeking to dismantle the contrivance that is the UK. It has, after all, only existed in its current configuration since 1922, with the term United Kingdom only being in use since 1801, with the beginnings of merging the many kingdoms across these isles only really beginning around 927.

The unity of the UK is clearly being stretched to close to breaking point over the past few decades and ever more so with the increasingly dysfunctional UK government dragging us out of the EU in such a shabby way, opening up every conceivable division amongst us, like festering sores. I am fairly confident that the UK will cease to exist in my lifetime.

Morocco is a similar contrivance, with its own unity also being questioned.

As with the UK, the lands saw many waves of invasions throughout antiquity. For Great Britain’s Celts, Romans, Jutes, Angles, Saxons, Vikings, and Normans, we have Morocco’s Berbers, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines and Arabs.

The Moroccan state appears to have been created around 790, with the creation of the first Muslim dynasty, focussed initially on the Roman-built city of Volubilis before they created their own capital city at Fez. Whether this was a single united state seems unclear as I find references to the Morocco emerging from a merger of smaller states in 1554. Some sort of federalism appears to have existed in between times.

Of course, having only around 50% sea borders, compared to G.B.’s 100% makes borders a bit more volatile over history, but they appear to have been remarkably stable, even after the ‘Scramble for Africa’ by European colonial powers. The main legacy of this period is the unresolved status of the territory known as Western Sahara. Both Morocco and Mauretania have claims over it. The (very few) people living there, or at least some of them, aspire towards full independence. Yes Western Sahara!!

Just as within the UK, with its English and Celtic regions, Morocco has its Arabic and Berber regions, although not with distinct borders.

And also similar to the UK are tensions around its membership (or non-membership) of a regional trading bloc of nations. For EU read AMU. The Arab Maghreb Union was established in 1989, at a summit in Marrakech, with the aim of creating a powerful economic bloc for its members (Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mauretania and Morocco – and Western Sahara by default. Egypt has applied to join but has yet to be admitted).

It seems to be a barely functioning entity, unlike the EU. I’m not sure why this is so, but I suspect ethnic tensions play a role. Historically, the Maghreb is the homeland of the Berber people, who now find themselves divided between these superimposed nations, and largely subjugated by an Arab ruling class. This has been quite nasty at times. For example, one of the things the AMU seems to have achieved was the banning of giving children Berber names!! The language was suppressed too, with it being banned in schools, despite it being the first language in many areas. Thankfully, Mohammed VI saw fit to lift these bans in Morocco in 2014. But these controversies will sound very familiar to my Welsh readers in particular!

Thus, the issues surrounding nationalism and ‘country’ are not dissimilar in both UK and Morocco. Being among the relatively few monarchical nations (I count just 24 living kings/queens/emperors currently) gives them something more than usual in common, but nonetheless, issues related to nationalism, cultural suppression, expansionism and/or separatism (they co-exist in our perceived global superpowers, for example) are found in virtually every nation-state. They are all political contrivances after all.

GOD

If issues around ‘country’ are similar between UK and Morocco, this cannot be said about ‘god’.

The demographics are stark enough.

Morocco claims to have been 99% Muslim for decades with the 1% containing Christians, Jewish and Baha’i in noticeable pockets.

The UK appears to be a rapidly evolving religious landscape:

The headline news is that for the first time in census history, less than 50% of the population of England & Wales identified as Christian in 2021. A fall from 59.3% to 46.2% in a decade is spectacular and represents a loss of well over 5 million Christians.

Even more gratifying, those identifying as having ‘no religion’ rose from roughly a quarter of the population to well over a third in those 10 years. That’s an increase of 8.5 million people, significantly from among those who preferred not to respond at all to this question in the past.

Countering these progressive trends, we do see increases all the major religions listed, and the ‘other religion’ category, which for the first time gave people the opportunity to record their actual religion. It makes for quite interesting reading, especially given my Coed Hills connections (paganism, wicca and shamanism show significantly).

But the overall direction of travel is clear enough. Having said that, I suspect that what has really happened is that people are simply feeling able to be a bit more open and honest about what they believe and therefore which box they tick. This is, I believe the big difference between the UK demographics and the Moroccan ones.

Over my lifetime, I don’t think adherence to Christianity has actually changed that much but what has changed, from generation to generation, is societal expectations. Once upon a time, it would have been expected that very English person would be an Anglican and it would have been difficult to say any different, although rival Christian sects like Roman Catholics, or Baptists would be tolerated (more in some places than others). I know for a fact that it was, and still is to only a slightly less extent, very difficult to come out as anything other than a Roman Catholic in Poland.

During my adult life, what we have seen happening is that the vast swathes of people christened into a Christian denomination in my generation, but not practicing in any way, used to still identify as being of their christened denomination. Overtime, however, these people have felt less and less inclined to be cajoled into the social convention of christening their babies at all, and thereby becoming not only increasingly likely to stop identifying themselves as Christians but producing children even less likely to identify with any religion.

What does the census data tell us? Well, that’s tricky because the first question about religion didn’t appear on the UK census until 2001, which simply gave the option of ticking one of seven boxes: Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, and None. Prior to this we have data from miscellaneous surveys of varying degrees of confidence levels and credibility.

I’m pretty sure that there is no data collected about religious affiliation in Morocco and that the 99% Muslim figure is assumed rather than counted. Not that I’m disputing that it wouldn’t indeed be close to this if it was put on a mandatory census form. I saw enough to recognise that it can’t be easy to identify as anything other than a Muslim, especially if you have been brought up as a Muslim. The 1% non-Muslim guesstimate is probably close to recorded immigration from non-Muslim countries. But to my mind this is all as credible as the Iranian government’s claim that there are no homosexuals in Iran.

Islam informs the societal norms in Morocco, as it does in all Muslim countries, but thankfully it is not enforced quite as oppressively. In fact, from what I saw, most Moroccans are tolerant and very hospitable. Everyone seemed to identify as Muslim, but they seemed pretty easy-going about it. I suspect most would get defensive if they had their religion questioned (I resisted the temptation), especially among the evidently more conservative older generation. That evidence was mostly in the way people dressed.

Clothes are a particularly important part of Moroccan culture and etiquette. Many Moroccans, especially in rural areas, may be offended by clothes that do not fully cover parts of the body considered “private”, including both legs and shoulders, especially for women. But instead of the burqa seen in more oppressive cultures, you will see the much more attractive djellaba or kaftan prevailing in Morocco among those more traditionally minded.

It is true that few Moroccan women wear a veil – though they may well wear a headscarf – and in cities Moroccan women wear short-sleeved tops and knee-length skirts and western fashionable clothes. But as a result, they may then suffer more harassment, which seems tolerated as if it is to be expected. It appears to amount to older men having a quick grope as younger more-scantily clad women pass by.

Men may wear sleeveless T-shirts and above-the-knee shorts without any such fears, of course.

This is just part of the divisiveness of religion. Older guys that pretend to be more traditional religious conservatives think they are morally superior and entitled to prey on the more liberal-minded, dare I say progressive youth. But at least it is not the oppressive state fundamentalism of some countries.

But what it suggests to me is that although, I suspect, every single Moroccan I encountered would self-identify as a Muslim if asked, I really do wonder about the deep-seated convictions in those claims. As I mentioned earlier, I hardly saw anyone even bat an eyelid during the calls to prayer being bellowed across their heads at regular intervals during every day. Its just part of the background noise. The mosques only appear to get filled on special occasions, and opportunities to flout rules like those over alcohol are always there and tolerated so long as you are reasonably discreet about it. After all, King Mohammed VI was something of a playboy in his princely days, by all accounts.

The way I see it is that the UK is much further down the path of throwing off the shackles of religion than Morocco, but it has taken small steps in that direction under its current monarch. Whether it maintains this trajectory remains to be seen, given the march of fundamentalism around the globe. The UK has its own challenges fending off right wing Christian Conservatives after all.

KING

So, what should we make of the monarchy and the monarchs in these respective countries? The first thing to make clear is the vastly different constitutional roles of the monarchs in the UK and Morocco.

In Morocco, the king has the final say on all major decisions, not just in theory, but in practice. The king personally chooses the Head of Government (Prime Minister) from the winning party of the legislative elections. He also chooses and appoints the foreign (Foreign Sec.), interior (Home Sec.) and finance ministers (Chancellor of the Exchequer). He can, and does, terminate their services when he so wants. He presides over the council of ministers (the Cabinet). He can dissolve both the upper and lower chambers of parliament. He is the supreme leader of the armed forces and controls appointments to the national bank. He can effectively set the agenda of government and does so. He currently has set an agenda aimed at reducing inequality, cutting poverty and fostering growth. This has made him widely popular!

Once upon a time, the UK monarch had similar power in a similar role. The UK monarch’s role in government today is purely symbolic. They formally open Parliament every year, and they rubber stamp (Royal Assent) Acts of Parliament, without any other input in the process. No monarch has refused to give Royal Assent since 1708.

So, our Charlie can, and does, have strong opinions on every subject under the sun, but that has no significant impact on anyone’s agenda, let alone Parliament’s. He is paid a small fortune out of the public purse, to add to his obscene inherited personal fortune, for the not-so-onerous tasks of going on the occasional walkabout amongst the peasantry, embarking on goodwill visits around the globe, hosting lavish receptions for foreign heads of state visiting the UK and basically just trying to behave and serve as part of Britain’s “national identity, unity and pride”, to quote the official royal website. He does fuck all of use to man or beast, to put it succinctly.

This being the case, it depresses me to see so many people supporting this medieval institution of inherited privilege. At least in Morocco the king does have to actually put a proper shift in occasionally. Dear old Liz was the very definition of inoffensive as she did at least know how to behave well. I was always surprised, however, that she seemed to get a free pass for marrying an obnoxious racist and bringing up a clutch of variously dysfunctional kids who we now have to put up with as the senior royals in the country. This will, I would hope and expect, see the popularity of the whole institution of the monarchy slowly but surely wane, to a point where, like religion, we can consign this anachronism to the dustbin of history, where it should long have been by now.

This reminds me; our monarch is also assumes the role of High Governor of the Church of England (but not head of the Anglican communion of churches across the world). Like the relationship with Parliament, the role is strictly a symbolic legacy of the formation of the Church of England when Henry VIII threw his toys out of his pram when the Catholic Church declined to allow him to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, for failing to produce him an heir (let alone a spare!). He had Anne Boleyn lined up, and had even been ‘test-driving’ Anne’s sister, Mary. Such are the shabby origins of this shabby institution. Thankfully, the church quickly distanced itself from the moral leadership of its founding figure and the Bishop of Canterbury came to be seen as the spiritual leading figure of the church, in an attempt to give it a sheen of credibility.

As we endure a daily media feeding frenzy around the hapless and nauseating Windsor family (currently focussed around Andrew trying to squirm out of his sex abuse settlement so he can return to the privileges of being Duke of York again and revelations from Harry (Hewitt or Windsor) about his penis) , surely the time has come for a mature conversation about bringing the farce to a dignified end and dragging the country into a more modern and progressive constitutional arrangement.

As with religion’s waning appeal, there are sure signs that Liz’s long overdue passing of the monarchical ‘baton’ to Charlie is causing the court of public opinion to shift decisively.

The Queen’s popularity ratings rarely fluctuated very much from these (YouGov) figures gathered not long before her demise (I believe):

But the King is starting off from a much lower popularity base:

He’s liked by close to half as many; actively disliked by close to three times as many; with three times as many indifferent. KCIII’s numbers suggest that we are not far from a position in which a referendum on abolition of the monarchy in the UK could be successful. I’m pretty sure an independent Scotland and Wales would not opt to keep any monarchy. Ireland opted for a republic over the monarchy thirty years after declaring independence. I don’t think we’d see it take that long in Scotland or Wales. England, being a right-leaning, Tory establishment-supporting enclave may well choose to kowtow on indefinitely.

In conclusion, I have always been against inherited wealth, inherited privilege and inherited power on principle. It goes against everything I believe in as an ecosocialist.

I fully recognise that it is a system that can sometimes work well and with the right people involved, can actually produce something akin to a successful socialist agenda. Morocco is trying quite hard to achieve this today.

In most parts of the world where monarchy persists, it has been marginalised to a representative role at best, and as such can be argued does little harm. I get sick of hearing how beneficial our monarchy is as a tourist attraction, which is a dubious enough assertion but a wholly irrelevant one, in any case, to the validity of the principles behind calling for its abolition.

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS

Morocco made quite an impression on me and gave me pause for thought on many things covered by this piece, among others too. It feels like a country relatively at ease with itself, with a current of mild optimism that things are slowly but surely improving for most people.

Of course, in just a couple of weeks doing a whistle-stop tour and encountering a limited range of people, I’m working on gut feelings and relatively superficial observations. But I sense a kind of mutual toleration and respect of each other between the majority of the people and the establishment entities of religion and monarchy. These establishment institutions seem to have the people’s best interests genuinely at heart. The people therefore are prepared to put their doubts and misgivings aside and forgive the establishment indulgences and extravagances. In return, the establishment institutions, secure in having mass support, do not feel they need to be over-zealous in enforcing discipline on the people. The over-arching impression I got was that life may be quite tough in some ways, but its okay and a lot better than it could be.

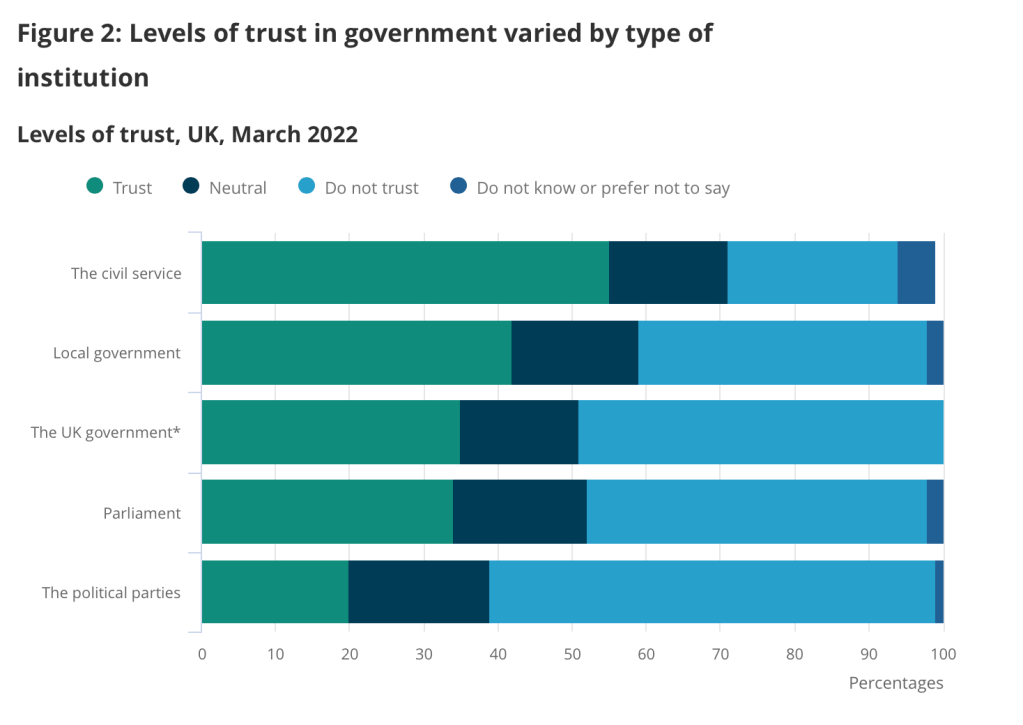

This is all pretty much the opposite of the zeitgeist in the UK these days, where we know it could be a lot better than it is. Trust in our politicians and establishment institutions has been eroded steadily during my lifetime. Even the governments own figures make damning reading:

Is there anything getting better in the UK right now? There must be, but I can’t think of even one right now.

Right-wingers will probably suggest that the erosion of respect for establishment institutions like church, monarchy, police etc. is responsible for the decline in standards in just about everything. This fails to understand that respect can only ever truly be earned and can never simply be commanded.

These institutions should only exist to serve the majority of the people and should only wield power with the consent, democratically given, of the people. This is where it has all gone wrong in the UK over the last 40 years or so.

In Morocco, church and monarchy still manage to maintain the support of the vast majority because they demonstrably work to try to improve the lives of the people for the most part. Or at least they succeed in giving this impression. This is a fragile state of affairs that has evolved over centuries but that could be destroyed very quickly (witness the other countries of North Africa).

The UK feels like it is already in the process of disintegration. This is the legacy of 40 yrs of successive neoliberal, capitalist governments that have successfully manipulated the democratic system to ensure they are unchallenged in any meaningful way.

Potentially at least, church and or monarchy could have stepped in and defended the interests of their congregations/subjects. History is light on examples of this ever happening effectively in the UK, and is hardly an example of effective democracy in any case.

Thus, it is hard to be optimistic about the long-term futures of either UK or Morocco. Morocco is only one tyrant away (in either church or monarchy) from disaster. The UK is past the point of no return and the only hope of salvation I can see is the dissolution of the UK through Scottish and Welsh independence, thereby allowing a constitutional clean slate to give us the opportunity to learn some lessons and do things very differently. Let it be.

A thought-provoking and well-written piece. I would expect nothing less. Thank you for sharing your experiences and opinions.

LikeLiked by 1 person