I’ve attended a few of the nigh-on-thirty National Marches for Palestine in London and many others in Cardiff. This is the first that has had me welling up in tears.

The first pro-Palestine demo I attended in London, maybe 10 years ago, had somewhere between 20 and 30 thousand marching. The monthly marches over the last 18 months or so have had between 80 and 200 thousand on them. With the news this week that Netanyahu is about to embark on the last phase of his project to ethnic cleanse the Gaza strip, there was the anticipation that there may be well over 200,000 there today from all over the country.

The whole atmosphere was a bit more intense, it seemed to me, as we slowly made our way from Russell Square to Downing Street, via my old stomping ground of Aldwych and the Strand

I suspect I was not alone on reflecting on the mounting horrors being committed in Gaza, with our government’s ongoing complicity, but also that today also marked the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki, three days after the bombing of Hiroshima. These war crimes killed 120,000 people instantly and hundreds of thousands more slowly and excruciatingly due to the aftereffects; more than everyone of us on the streets of London today. We didn’t get to see people dying excruciating deaths on our screens in 1945; most didn’t own any screens back then (there were less than 10,000 televisions in the UK in 1945). Now we get to watch genocide, including the starvation of children, in real time on all our many screens.

The other undercurrent today was that this was the first time many of us had been on such a demo since the proscription of Palestine Action. Most of those attending would be supporters, in principle at least, of Palestine Action’s cause, but all now were wary of falling foul of interpretations of this and facing the prospect, and consequences, of being arrested, labelled a terrorist sympathiser and facing a potential 14-year term of imprisonment. Add all this together and is it any wonder that the mood was even more sombre than usual.

Because of concerns about conflating the issues of the Gaza genocide and the UK civil rights oppression, support for Palestine Action was organised in a totally different way, such that those that didn’t want to get caught up with opposing the proscription were in no danger on the main march. Indeed, the policing of this march was very low key and discreet. This was in sharp contrast to the Palestine Action support protest.

While the National March saw perhaps 200,000+ people congregate in Russell Square to commence the March at exactly 1pm, two miles away in Parliament Square 500 briefed and prepared volunteers awaited Big Ben to chime 1pm, sat down on the grass, and unrolled their own hand-written A2 posters, all saying exactly the same thing:

I got to Parliament Square about 2.30pm by which time those sitting in the square and a whole lot more people, including a lot of journalists and camera operators, were effectively kettled by a ring of around 200 police officers. I asked if I could join my friends inside the cordon and was told in no uncertain terms “No”. When asked why not, all I got from the Met officers was that “A section 13 of the Public Order Act is in place.” When I asked what that was the Met officers refused to say and just said “Look it up”.

I wandered around the cordon until I stumbled across a whole section, in front of the Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi statues, ironically enough, that consisted of officers from Wales! They were very conspicuous due to the HEDDLU labels, but also much chattier (would you believe that!). Chatting to a few of them, I clarified that my placard would likely not get me arrested today as it is ambiguous enough as to whether I was expressing support for Palestine Action, and they had plenty of unambiguous ones to sort out first. I asked her if I verbally removed the ambiguity and told her I supported Palestine Action, would she arrest me. She said that that still would not be a priority today. Oh well, I tried!

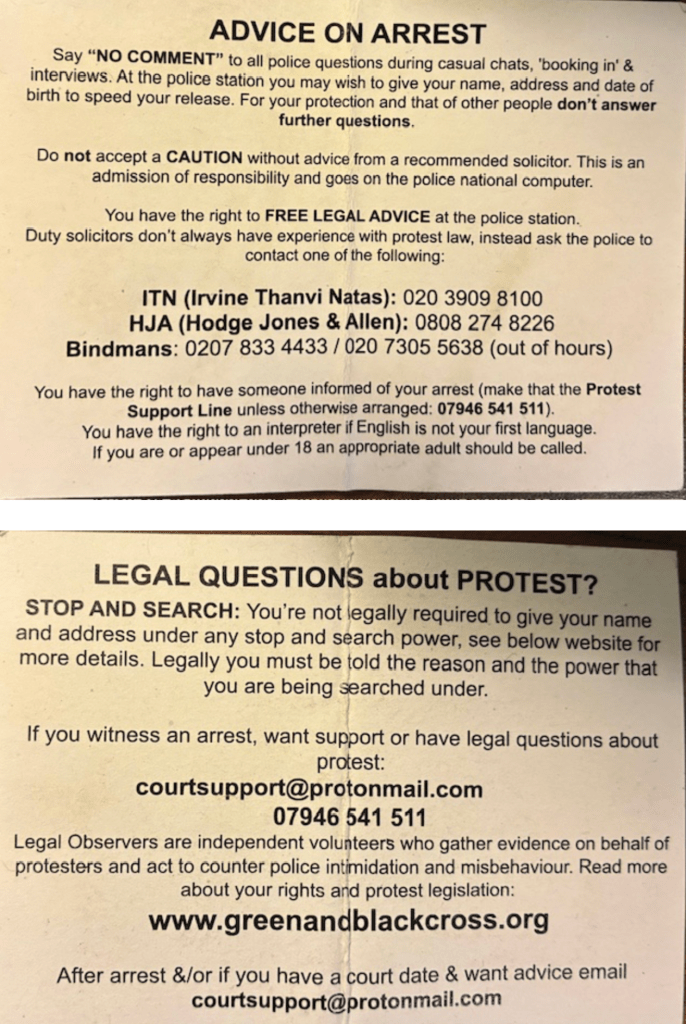

Many of you reading this will know how embarrassed I have become over the years at never having been arrested on a demo. Despite the impression I may have given above, I had already determined that I didn’t really want to be arrested today. I had had a long chat with a couple of the legal observers that are present at all such demos about the changing climate around the criminalisation of protest in the UK, specifically the Palestine Action situation.

The implications of being arrested and either accepting a caution or being prosecuted and found guilty of supporting a proscribed organisation can be dire. It was not anticipated that mere supporters, as opposed to members and/or participating activists, were likely to be jailed, but even a mere caution stays on your record for 10 years and could have serious career and other ramifications for many, and also incur travel bans to many countries. I have no career worries anymore, but I do still have plenty of travel plans!!

The legal advice around being arrested has been the same for years. Below is an up-to-date copy of the cards the legal observers hand out on demos. The only thing that has changed is the phone numbers and email addresses, so if, like me, you have been carrying one of these in your wallet/purse for years, you might want to check you have the current contact details.

I’m sure all of those arrested in Parliament Square today will have had them. Because of the consequences outlined above, the 500 volunteers will have all known the possible consequences and how to handle the near-inevitable arrest. Perhaps because of this, the demographics of these 500 people are a bit different to most people I have seen arrested at demos over the years.

As of 10:00pm this evening, 474 people had been arrested in Parliament Square, according to the BBC. That number had been 365 at about 8:00pm. I witnessed about 30 arrests myself, between 2:00pm and 4:00pm.

The first person I saw being arrested (above) was this smartly dressed gentleman. I was told that he was a solicitor. Apparently, one of the first arrested, before I got there, had been an elderly gentleman in a wheelchair. I was a bit sceptical of this story initially, but then witnessed many elderly people, especially women in (I’m guessing) their 80s being bundled off into police vans. There were university lecturers, vicars, self-employed professionals like dentists and accountants, many retired people from all walks of life and a smattering of smart, articulate young people all prepared to stand up (or be dragged away) and be counted.

It was this spectacle that I was surprised to find had tears rolling down my cheek at one point. These people were guilty of no more than supporting efforts to end a genocide that is occurring before our eyes. They were being labelled as supporters of terrorism by a government arming the genocidal regime and effectively condoning (through Palestine Inaction) the ethnic cleansing and bulldozing of Gaza to enable its annexation and redevelopment as luxury seafront real estate for wealthy Israelis and American tourists. Trump can’t wait to get involved!

WTF has the UK become?

After so many years of Tory incompetence and corruption, we now have an even more disgusting Labour government continuing with austerity for the poorest while Starmer’s net worth of well over £10m rapidly starts chasing after Tony Blairs obscene £50m+ and the guy knighted for service as a human rights lawyer tuns into an Orwellian “Big Brother” proscribing direct action way less damaging than that he worked hard and successfully to get cleared in courts of law little more than 20 years ago. Nauseating!

Starmer and Cooper may yet be forced to rescind the proscription of Palestine Action, despite Cooper doubling down on it today. On 30 July, a High Court judge ruled that Palestine Action can bring a legal challenge against the UK government over its designation as a terrorist organisation. This followed a hugely damning statement from Volker Türk, High Commissioner for Human Rights at the United Nations that says:

“UK domestic counter-terrorism legislation now defines terrorist acts broadly to include ‘serious damage to property’. But, according to international standards, terrorist acts should be confined to criminal acts intended to cause death or serious injury or to the taking of hostages, for purpose of intimidating a population or to compel a government to take a certain action or not. It misuses the gravity and impact of terrorism to expand it beyond those clear boundaries, to encompass further conduct that is already criminal under the law.”

This Labour Government is not just nauseating, but it almost as embarrassing as the Johnson government.

Just to lighten the mood a tad, let me share two true stories from today of arrests that made me chuckle. These were not in Westminster Square but on the National March. These were people whose placards were deemed less ambiguous than mine in their support for Palestine Action. Both were dismissed when taken for processing with the arresting officers rebuked for their illiteracy, I warrant. The first went something like this:

That’s one officer now aware of the importance of commas!

The second one I heard about and struggled to believe, but then I bumped into the guy and took his picture! Hopefully you’ll spot the issue quicker than the arresting officer!

But my final memories of the day occurred on my journey back home, and again had me welling up.

The first occurred on the tube from Westminster to Paddington. I was sat opposite a lady wearing a hijab and she read my sign and I saw a tear roll down her face. She stood up to get off at the next stop and leaned forward towards me and simply said “Thank you, thank you”.

The second occurred on the train out of Paddington, less than an hour later. There was a lady about my age, travelling alone, sat across the aisle from me but facing me. This was the conversation, initiated by the lady, with an east European accent:

“Excuse me, can I ask you something?”

“Sure.”

“Do you hate the Jews for what they are doing in Gaza?”

“No, not at all! What is happening in Gaza is not the doing of the Jewish people, but of a genocidal rogue state.”

“Thank you. I agree with you.”

We said no more, and she got off at Reading.

What a day.

PS. A guardian article, a week later, about some of the older generation who were arrested: