I’ve recently returned from a trip to Argentina that saw me visit Buenos Aires, coastal Patagonia and Ushuaia, Terra del Fuego. I quickly felt more comfortable identifying as Welsh rather than British, not because I was in any way intimidated or threatened (quite the contrary), but simply because of historical evidence and propaganda everywhere I went.

Before I delve into this further, let me present some historical context.

Argentina was, of course, initially part of the Spanish Empire, but parts of Argentina, such as Rio de la Plata (including Buenos Aires) and Islas Malvinas (a.k.a. Falklands Islands), were squabbled over between the Spanish and British in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Argentina’s current borders were settled after its War of Independence that saw it declare independence from Spain on 15 December 1823. Britain stayed neutral in the war but was quick to recognise the newly established republic. Argentina effectively shelved its claims of sovereignty over the Falklands in return for British economic investment that played a major role in the Argentine economic boom that lasted from the mid 1800s through the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Things changed after WW2 (during which over 4000 Argentine volunteers served with British armed services). The British policy of ‘Imperial Preference’ directed most of its overseas investment to its colonies. The Perón regime then nationalised many British-owned industries, further diminishing British influence.

By the mid-1960s, the military were calling the shots and there was a military coup in 1966. The military junta soon saw value in resurrecting claims of sovereignty over the Malvinas/Falklands.

Initially, and under pressure from the UN, the British government, or the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) at least, saw the islands as more of a nuisance and obstacle to trade in South America and were inclined to cede the islands to Argentina in 1968. Parliamentarians sympathetic to the plight of ‘British’ islanders, frustrated these plans.

Thus, throughout the 1970s (and both Labour and Conservative governments) the Argentine government were kind of teased about British willingness to cede the islands once political issues in the UK were resolved. The FCO even tried to make the islanders more amenable by allowing Argentina to increasingly supply the islands with things like oil and food, hoping they would feel increasingly dependent on Argentina and less dependent on the UK.

In 1980, a year into Thatcher’s first term, her foreign secretary, Nicholas Ridley was despatched to the Falklands to try and persuade the islanders of the benefits of a ‘leaseback’ scheme. It failed, despite Ridley conceding in private that he knew that the Argentines were running out of patience and could decide to invade and take the islands.

For the Argentine junta, things came to a head in 1981, They had been in charge for 5 years and the economy had stagnated and was crumbling. Large-scale civil unrest was erupting all over the country. The new junta head, General Galtieri, needed a PR boost and hoped to divert public attention from the floundering economy and human rights issues by mobilising the long-standing patriotic sentiments of Argentinians towards Las Malvinas. He and his advisers were convinced that the British would never respond militarily. They had miscalculated.

By 1982, Thatcher’s popularity was plummeting, and the Falklands looked a no-win situation that could sink her completely. Quietly ceding the islands was one thing, seeing them invaded and snatched away was quite another. But going to war over them, given the logistical challenges involved and the lack of a certain outcome seemed crazy. However, ten weeks later, the Falklands were retaken, and Thatcher could do no wrong for most Brits.

But the Argentinians have never lost the conviction, so successfully embedded in them ever since the 1970s, that Las Islas Malvinas belong to them. The British, meanwhile have become ever more aware to the potential riches in the relatively shallow waters of the seas around the Falklands, and potentially in Antarctic territory beyond. Positions have become re-entrenched. However, we see or hear very little about the Falklands back in the UK these days. It is very different in Argentina, as I saw with my own eyes while travelling around. I became increasingly gob-smacked. Here are just some of my photos, firstly from Buenos Aires:

Just 100m from my Buenos Aires AirBnB. 8ft tall 4-sided memorial. The other three sides list the Argentinian ‘heroes’ who gave their lives. Why 2009? I don’t know. There are countless other memorials dotted all over the city.

At least half the buses in Buenos Aires had this stuck on the side. A law passed in 2014 by the Argentine Congress says public transport must have signs saying “Las Islas Malvinas son Argentinas” (‘the Falkland Islands are Argentine’).

I went to a Boca Juniors game in January 2025. An essentially left-wing club in the dock area of the city still has banners at home games asserting the Malvinas are Argentinian.

Moving on to Welsh Patagonia, I wondered if the strong Welsh affiliations and affections altered the attitudes towards the Malvinas/Falklands. Nope, not at all.

This adorns the Town Hall in Trelew. It was the only conspicuous memorial I stumbled across in this town, but some buses in the town had the same poster as those in Buenos Aires. Why 2024? Again, I don’t know.

The county town of Rawson, nearer the coast, ramped things up a bit more. Near the County Hall is an extensive collection of Malvinas memorials:

Translating the plaque beneath one of them:

Worker stopping with one hand raised

The advance of the internal and external enemy

That oppresses the people

And with one hand pointing

A barbed wire fence

Symbol of invading capitalism

Towards South American territories.

That’s the working classes of South America resisting the capitalist colonialists of Europe, Britain specifically in this case. Which is an interesting perspective for people largely descended from capitalist colonialists of centuries gone by, Spain in that case, but hey!

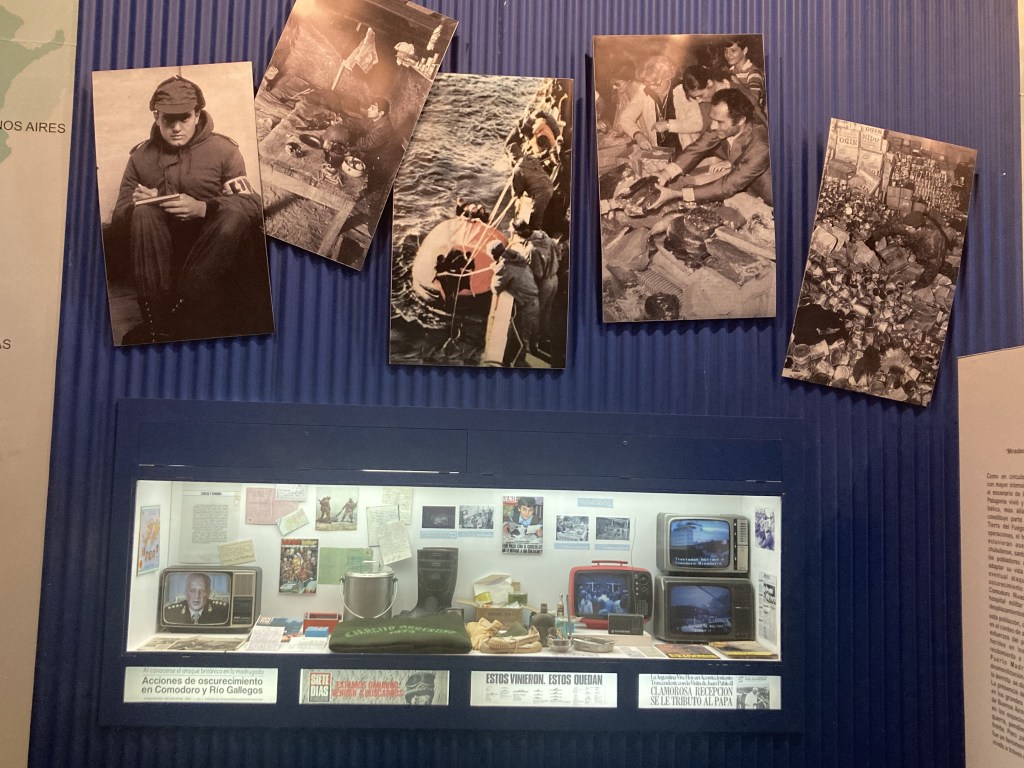

Rawson is also home to a museum dedicated to the Falklands War; the ‘Museum of the Malvinas Soldiers’:

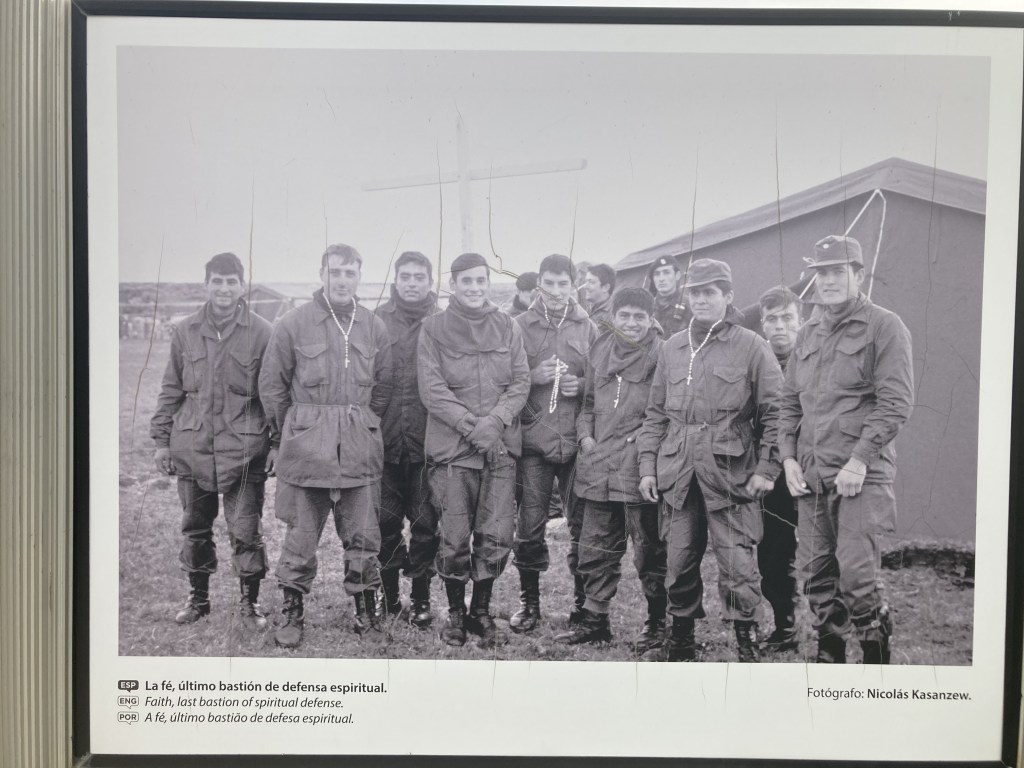

It appears to have been put together and curated by local families of soldiers who lost their lives there. It is, however, free to enter and I guess is financially supported by government at some level. It was staffed by a man in his 30s; quite an intense guy who recognised my Welsh soccer shirt. He got a bit emotional when I shook his hand and said ‘muchas gracias’ as I left.

Soldier of my country…

Boy of my people…

What unfathomable nights

your dreams sheltered!

I cry for you at night and…

At dawn I still remember…

Emotional stuff. But looking at the visitor book, I don’t think this museum sees many visitors. It is the public displays in the town centres that (a) keeps the emotion alive for the locals, but also (b) smacks the visitor in the face, especially British visitors. And thus, onto Ushuaia!!

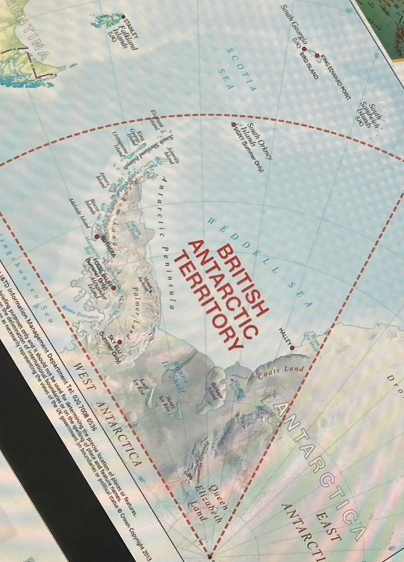

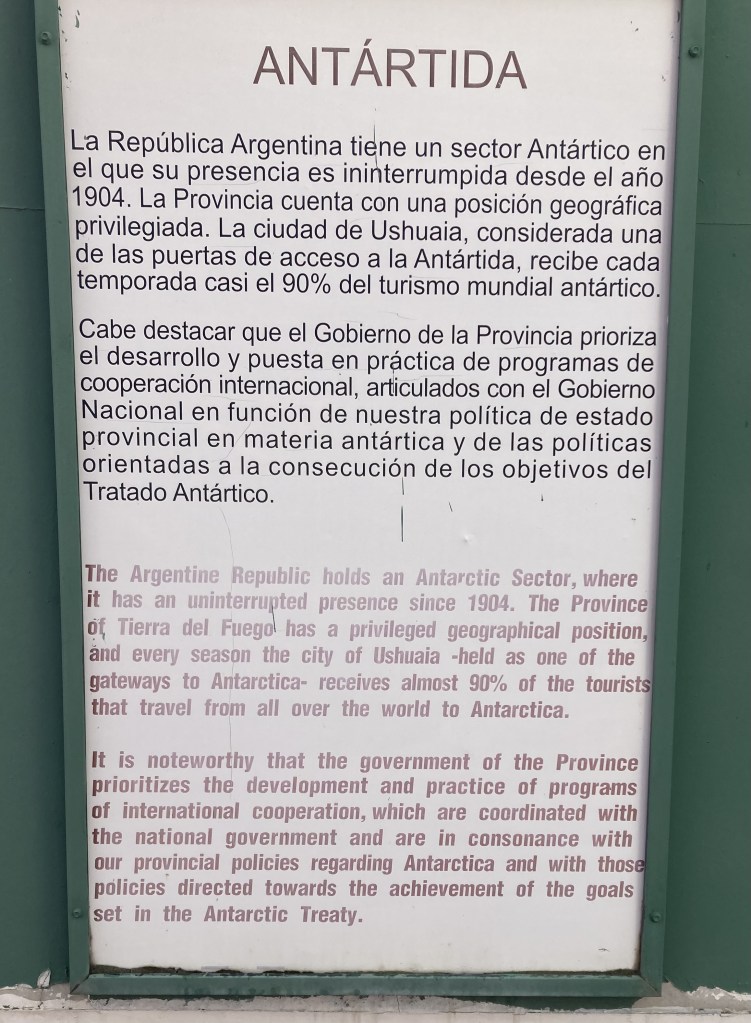

There is a special context to Ushuaia’s obsession with Las Islas Malvinas. This map, cut into thick sheet steel, is down by the port entrance:

Ushuaia is on Tierra Del Fuego in the top left of these maps. The Argentinian Government regards it as the capital city of all the territories on this map, thereby including the following territories that the map on the right identifies as UK territories: Islas Malvinas a.k.a. Falkland Islands, Islas Georgias del Sur a.k.a. South Georgia, Islas Sandwich a.k.a. South Sandwich Islands, Islas Orcadas a.k.a. South Orkney Islands and Antartida Argentina a.k.a. British Antarctic Territory.

Ushuaia doesn’t even attempt to perform any governmental functions outside of Tierra del Fuego as it regards these other territories as under illegal occupation by the British. But this doesn’t stop it attempting to maintain communications, if only via radio:

This is Nacional FM broadcasting from Ushuaia across Tierra del Fuego and, it would seem, to the Islas Malvinas. It would be interesting to know the listening figures from there!

But there are ‘in-your-face’ messages all over town:

Clockwise from top left: Memorial plaques from all manner of organisations / Entrance to large memorial plaza / Eternal flame in memory of the dead built at the 30th anniversary of the war / 40th anniversary war memorial / one of about twenty poster size photos displayed around the plaza.

And it is not just war memorials. In an attempt to assert that the Malvinas are theirs, there are also big diplays about the wildlife, ecology and need for ‘proper’ conservation on the islands:

There are a lot of references to “Argentinas y Fueguinas” to emphasise that the islands are not just Argentinian, but more specifically of the Tierra del Fuego administartive area, of which Ushuaia is the capital.

This was on the back of business premises overlooking the port.

Next to the port entrance, and elsewhere, there are lots of things stressing that the Islands are relatively close to Ushuaia (but that is still about 500 miles), compared to Buenos Aires, and also that the UK is ridiculously far away; 12,700km or 7,900 miles.

Also next to the port entrance, and quite pointedly in both Spanish and English, given the large number of English-speaking tourists passing through, are these two unequivocal statements on large noticeboards:

I would love to know what has been deleted from the bottom!

So, the message is loud and clear and unequivocal; Argentina has not given up on being able to assert sovereignty over the Falkland Islands, at the very least, and over other UK held territories in the South Atlantic/Southern Oceans.

However the language used by the current President (at the time of writing), Javier Milei, has been tempered compared to some of his predecessors. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ce43zv3qln9o

There clearly is no desire to physically fight over the islands again. But it is also clear that a diplomatic resolution is nowhere near even being on the horizon again. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ce43zv3qln9o

In the meantime, a two prong PR campaign that has been going strong since the 1970s continues. First is all the messaging on public transport and public buildings aimed at keeping the idea firmly implanted in the mind of the Argentinian public. Second is the uncompromising messaging to visitors to Argentina, especially conspicuous around ports and airports used by tourists, presented extensively in English so that British and American visitors, in particular, cannot miss the message.

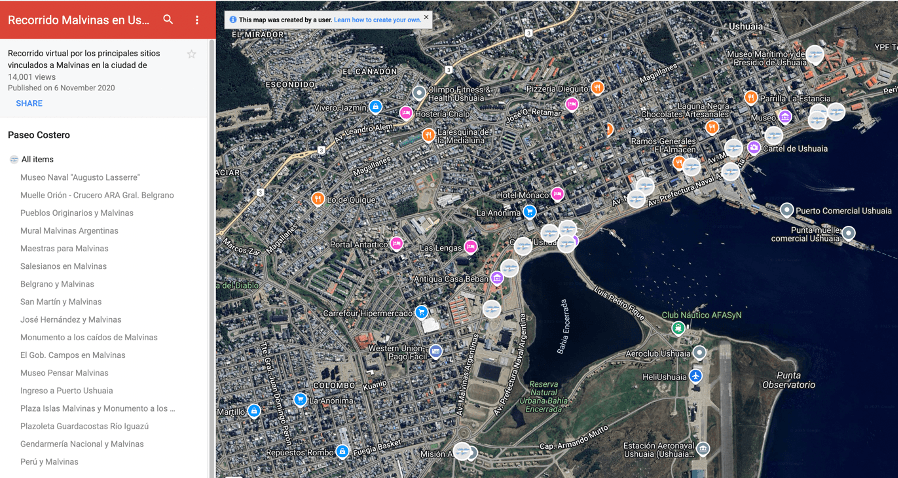

Here is the main tourist information online portal for Ushuaia:

The map link at the bottom goes to the map below that shows the whole array of public installations to do with Las Malvinas, but which is far from inclusive of all mentions of Las Malvinas around the town.

So, what do I conclude about the Las Malvinas/Falklands situation now, in 2025, well over 40 years since the war?

British tourists, as far as I can see, and in my experience, suffer no discrimination from the Argentinian hospitality sector, nor from the vast majority of the Argentinian people. There seems to be an understanding about the capitalist interests driving the current determination of the UK establishment to hold onto the Falklands and other territories in the region. But it is this feeling that they are being robbed of potential resources that belong to them that will not let them give up on the aspiration to have sovereignty over the islands recognised and achieved.

There is no hint of any desire to go to war over the islands again right now, but in this age of Trumpian powder-keg diplomacy, that could change if the conditions were right, and some sort of trigger event occurred. There are possible trigger events on the horizon such as the uncertain future of the Antarctic Treaty’s Environmental Protocol when I it comes up for review in 2048.

Perhaps even more imminent is the “Blue Hole” issue of the fishing free-for-all going on around the Falklands due to the waters being caught in the middle of the territorial dispute between the UK and Argentina. One of the consequences of this is the lack of any agreements on fishing in these waters; it is one of the only areas of sea not covered by any regional fishing agreement. The consequences of the resultant over-fishing are dire for Falkland Islanders (the fishing industry makes up two-thirds of the Falkland Island’s economy) but also for the impact on fish stocks in neighbouring waters. https://www.ethicalmarkets.com/falkland-islands-dispute-is-causing-fishing-free-for-all-in-nearby-blue-hole/

This may yet convince the Falkland Islanders that their prosperity and future might actually be more secure under Argentinian jurisdiction. This was, after all, an argument the UK Governments put forward themselves back in the 1960s and ’’70s, remember?

That would be a fascinating turn of events given that the (duplicitous) pretext for fighting the war in 1982 was the Islanders explicit desire to stay ‘British’. If they were to change their minds (and Shetland/Orkney Islanders, for example, are increasingly changing their minds and considering to self-determine themselves as Norwegian instead of British), then how could the UK say ‘no’? The UK is destined to dissolve in any case, sooner or later, with Scottish and Welsh independence and the re-unification of Ireland. Where this would leave British dominions and far-flung overseas territories, such as the Falklands, is an interesting consideration. The UK has only recently (just 6 months ago, in October 2024) given sovereignty of the Chagos Islands back to Mauritius. This is a interesting precedent. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c98ynejg4l5o

It is my view that there is natural justice https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_justice that should ultimately settle all such issues, if and when a fair and balanced consideration of material facts and human and environmental impacts can hold sway. I do not wish to prejudge such things, but nonetheless, I am of the opinion that this would lead to not just the dismantling of the UK as described above, but also the recognition of islands that cannot (or want not to) sustain themselves as independent nations belonging to the nearest and/or geologically consistent land mass country.

Thus, I do think that eventually the Falkland Islands should and will become recognised as Las Islas Malvinas of Argentina.

But what of the Islanders desire to remain ‘British’? A major part of this is cultural. They are almost all of British descent; English-speaking, but mostly descended from Scottish and Welsh immigrants who settled from 1833 onwards. More recent immigrants have stemmed the population decline in the islands and have come mostly from the UK, St Helena and Chile. The 2012 census https://web.archive.org/web/20130520184434/http://www.falklands.gov.fk/assets/Headline-Results-from-Census-2012.pdf showed 59% of residents identifying as Falkland Islanders, 29% as British, 9.8% as Saint Helenian and 5.4% as Chilean (N.B. adds up to more than 100% as some identified as belonging to more than one category). A small number identified as Argentinian and of other nationalities.

I deduce a few things from these figures. Firstly, the Islanders do not see themselves as essentially British; they see themselves as essentially unique and distinct. Secondly, beyond the cultural matters of language, religion (most are protestants), and education, their loyalty to Britain is probably essentially pragmatic – that the UK guarantees its well-being and security to the tune of £60m a year, not counting major infrastructure investment of military significance, such as the recent £7m refurb of the Mount Pleasant military base. That represents more than £30,000 a year for each full-time inhabitant. (For context, that £60m could cover the £20 increase in Universal Credit given during Covid but since removed despite no end to the cost-of-living crisis. Or free school meals for 150,000 kids. But hey, I digress).

The point is that I feel sure that the islanders could easily be convinced that their livelihoods (mostly fishing dependent) and well-being (access to healthcare especially) could easily be matched, if not bettered by being under Argentine jurisdiction, and that assurances and guarantees about preserving their cultural identity and ways of life as English-speaking, tea-drinking, Anglicans would be enough to seal the deal.

After all, there is another part of Argentina that has done just that for another group of settlers of British descent, namely Welsh Patagonia.

Which brings me neatly to my reflections on what I saw and learned in and around Welsh Patagonia.

Welsh Patagonia is generally recognised as coinciding with the Argentinian province of Chubut. Having initially landed at Puerto Madryn, the early settlers were guided to the more fertile land along the lower Chubut valley by the indigenous Tehuelche people, thereby creating the towns of Rawson (named after Guillermo Rawson, the Argentine Minister of the Interior who championed and supported the Welsh settlement in Argentina), Trelew (initially Trelewis, the Welsh for Lewistown – a village just outside Bridgend), Gaiman (the name originating from the Tehuelche place-name meaning “rocky point”), and Dolavon (derived from the Welsh for “river meadow”). These are the five towns I visited.

Sometime later Welsh settlers migrated across the pampas and set up towns in the foothills of the Andes, such as the initially flour-milling town of Trevelin (from the Welsh ‘Trefelin’ = mill town) and Esquel (derived from Tehuelche words for “marsh” and ‘thorny plants”). I didn’t have time to get to these towns.

The story of the Welsh arriving in Puerto Madryn is a sad one.

The onset of the Industrial Revolution saw wealthy English capitalists investing heavily in the South Wales coalfield valleys and saw mass migration into the area. Welsh speakers became a nuisance and began being persecuted not just in the workplaces but by parliament. An 1847 parliamentary report on Welsh education (that became known as the ‘Treachery of the Blue Books’) https://www.library.wales/discover-learn/digital-exhibitions/printed-material/the-blue-books-of-1847 poured scorn on Welsh speakers and advocated punishments like the ‘Welsh Not’; a piece of wood hung around the necks of children caught speaking Welsh.

This persecution saw many join the waves of migration to America, but this didn’t make it easier to maintain the speaking of Welsh (although they did create ‘Welsh’ towns at Utica in New York State and Scranton in Pennsylvania). The idea of creating a remote utopia away from the influence of the English language became an obsession for some.

One such was a Caernarfon publisher and printer, Lewis Jones (honoured in the naming of Trelew), who in 1862 travelled to Patagonia’s Chubut Valley, accompanied by Welsh Liberal politician, Sir Love Parry-Jones (whose home estate, Madryn, would give its name to the port in which the settlers would land). They met with Guillermo Rawson, the Interior Minister, and he was amenable as he saw it as a way of gaining more control over a large tract of land disputed with their Chilean neighbours.

Having obtained Rawson’s agreement, the next step was to round up a group of initial settlers. A Welsh emigration committee met in Liverpool and published a handbook, Llawlyfr y Wladfa (Colony Handbook) to publicise the Patagonian scheme. The handbook was widely distributed throughout Wales and in America.

The first group of settlers, over 150 people, gathered from all over Wales, but mainly north and mid-Wales, sailed from Liverpool in late May 1865 aboard the tea-clipper Mimosa. Passengers had paid £12 per adult, or £6 per child for the journey. Blessed with good weather the journey took approximately eight weeks, and the Mimosa eventually arrived at what is now called Puerto Madryn on 27th July.

Unfortunately, the settlers found that Patagonia was not the friendly and inviting land they had been expecting. They had been told that it was much like the green and fertile lowlands of Wales. In reality it was barren and inhospitable windswept pampas, with no water, very little food and no forests to provide building materials for shelter. Some of the settlers’ first homes were dug out from the soft rock of the cliffs in the bay. I learned most of this from the Museo Del Desembarco:

Those shallow hollows where those first dishevelled migrants landed were the homes for most of them for a quite a few weeks, such that they cut out discernible recesses to act as shelves etc.

The future looked bleak, but the indigenous Teheulche Indians took pity on them and tried to teach the settlers how to survive on the scant resources of the area. This was my view of the area as I flew into Trelew.

They essentially survived by receiving several mercy missions of supplies until, with Tehuelche help, they identified a hopefully viable proposed site for the colony in the Chubut valley, about 40 miles from Puerto Madryn. It was here, where a river the settlers named Camwy cuts a narrow channel through the desert from the nearby Andes, that the first permanent settlements of Rawson and Trelew were established from the end of 1865.

The colony suffered badly in the early years with floods, poor harvests and disagreements over the ownership of land. In addition the lack of a direct route to the ocean made it difficult to bring in new supplies; Puerto Madryn remained the best landing point in the region.

History records that it was a certain Rachel Jenkins who first had the idea that changed the history of the colony and secured its future. Rachel had noticed that on occasion the River Camwy burst its banks; she also considered how such flooding brought life to the arid land that bordered it. It was simple irrigation (although backbreaking work to create) that saved the Chubut valley and its small band of Welsh settlers.

This history is preserved in Trelew’s ‘Pueblo de Luis Museum’ named in tribute to Lewis Jones (‘The people of Lewis’ Museum), based in what was the railway station eventually built for the line up the valley.

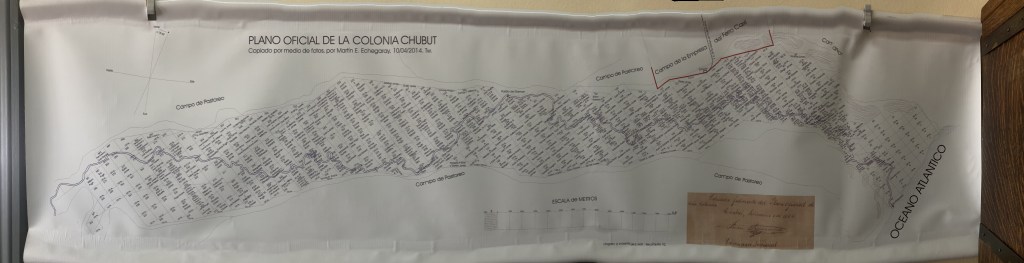

Over the next several years new settlers arrived from both Wales and Pennsylvania, and by the end of 1874 the settlement had a population totalling over 270. With the arrival of these keen and fresh hands, new irrigation channels were dug along the length of the Chubut valley, and a patchwork of farms began to emerge along a thin strip on either side of the River Camwy. The plan of the plots is in the museum. It appears that many changed their first names to Spanish equivalents – John Evans becomes Juan Evans, William Thomas becomes Guillermo Thomas, Henry Griffiths becomes Enrique Griffiths.

In 1875 the Argentine government granted the Welsh settlers official title to the land, and this encouraged many more people to join the colony, with more than 500 people arriving from Wales, including many from the south Wales coalfields which were undergoing a severe depression at that time. This fresh influx of immigrants meant that plans for a major new irrigation system in the Lower Chubut valley could finally begin.

There were further substantial migrations from Wales during the periods 1880-87, and 1904-12, again mainly due to depression within the coalfields. The settlers had seemingly achieved their utopia with Welsh speaking schools and chapels; even the language of local government was Welsh.

In the few decades since the settlers had arrived, they had transformed the inhospitable scrub-filled semi-dessert into one of the most fertile and productive agricultural areas in the whole of Argentina and had even expanded their territory into the foothills of the Andes with a settlement known as Cwm Hyfryd. Bridgend boy, John Murray Thomas was prominent in this expansion, with his story told in the museum:

He was born in 1847 in Penybont ar Ogwr, South Wales. He arrived in Chubut on board the Mimosa in 1865. He was married to Harriet Underwood. From 1877 onwards he made several exploratory trips through the interior of Chubut, highlighting the expedition led by Fontana in 1885 which resulted in the discovery of the Andean valleys and the subsequent founding of the Colonia 16 de Octubre, seat of Esquel, Trevelin and the Futaleufu dam. He died on 3 November 1924 at the age of 77 and his remains rest in the Moriah Chapel cemetery.

These now productive and fertile lands started to attract other nationalities to settle in Chubut and the colony’s Welsh identity began to be eroded. By 1915 the population of Chubut had grown to around 20,000, with approximately half of these being foreign immigrants.

The turn of the century also marked a change in attitude by the Argentinian government who stepped in to impose direct rule on the colony. This brought the speaking of Welsh at local government level and in the schools to an abrupt end. The Welsh utopian dream of Lewis Jones et al appeared to be disintegrating.

Welsh however remained the language of the home and of the chapel, and despite the Spanish-only education system, the proud community survives to this day serving bara brith from Welsh tea houses and celebrating their heritage at one of the many eisteddfodau.

Speaking to locals in all of the towns in the area, it is amazing how many proudly claim to be descendants of early Welsh settlers, and especially of those first 150 or so on the Mimosa. They seem proud of the story and declare that they would love to visit Wales one day. Most learned a bit of Welsh in school, but I found nobody claiming to be proficient in the language, although I was told that they do exist.

The future of the language in the area will need some help, as it has back in Wales. In 1997 the British Council instigated the Welsh Language Project (WLP) to promote and develop the Welsh language in the Chubut region of Patagonia. Within the terms of this project, as well as a permanent Teaching Co-ordinator based in the region, every year Language Development Officers from Wales are sent to ensure that the purity of the ‘language of heaven’ is delivered by both formal teaching and via more ‘fun’ social activities, especially eisteddfodau. Whether this will be enough, only time will tell.

So, and in conclusion, what, if anything, does the history of the Welsh in Patagonia have to say of relevance to the future of the British in the Falklands?

I think the essence of it is that anything is possible with a combination of the determination of the players to make things work and a degree of political expediency for the powers that influence things to allow things to work.

The Welsh settlers in Patagonia were political refugees escaping persecution in their homeland and determined enough to make a fresh start that they could find away to overcome the problems they encountered, with a little help. It was politically expedient for descendants of the Spanish colonialists to ‘give’ the land of the indigenous Tehuelche to this ramshackle bunch of refugees. The Tehuelche saw the benefits of the new trading opportunities and the land was not precious to them in any case. Everyone was a winner.

The context in the Falklands is very different of course. The settlers there were sponsored and supported by the British government, and still are to this day. There is no reason why, with the right mindset of the islanders and the Argentinians that the Islanders cannot prosper under Argentinian governance. Finding the political expediency to allow this to happen is likely to be relatively easy in Argentina. I get the impression that allowing the Islanders to remain and allowing them to maintain their language and cultural identity would not be a big issue in finding a settlement. As in Chubut, it might get eroded over time, but that depends on how strongly it is practiced and maintained. Getting British Government support might prove trickier – despite the attitudes it presented back in the 60s and 70s – as it is in the grip of rabid neoliberal capitalists who control the zeitgeist. But this has to change sooner or later.

My experience of Argentina is that Argentinians welcome and value British visitors and have no issue accommodating them as residents either, allowing them to be themselves. The issue between the countries is at Governmental level and focussed on the territorial disputes off the shores of Argentina.

Self-determination is a very important principle. It was denied to Welsh speakers in their homeland. Their determination to create a new homeland far away eventually succeeded because that determination was given self by the Argentinian respect for what they wanted to do in difficult terrain and respect and help offered both ways between those settlers and the indigenous Tehuelche people of the area.

Self-determination was given as the main reason for the military response of the British in 1982. While I may scoff at the notion that this was the primary motivation, it is an honourable enough motivation in most circumstances. We can argue about the legitimacy of self-determination claims of people shipped many thousands of miles to lay claim to uninhabited land, but if we put this aside, the most likely resolution of the dispute over the Falklands/Malvinas, in my opinion, is for the Islanders to come to the decision that they would prefer to be governed and supported by Argentina than the UK.

The Welsh migrants had had enough of British rule harming their way of life. The independence campaigns in Wales and Scotland are focussed on the conviction that living standards and well-being can be better once divorced from British/UK rule. The Northern Irish are coming around to the conclusion that they would be better off being part of a reunited Ireland, divorced from British rule. Shetland and Orkney Islanders https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-66066448 are actively exploring the benefits of divorcing from the UK and returning to Norway (they were Norwegian for 500+ years from the 10th to 15th centuries). Being part of the UK is patently less desirable as time goes on, and there is no sign of that changing any time soon. Once the UK crumbles I foresee the Falklanders quickly accepting the inevitable.

“I found nobody claiming to be proficient in the language, although I was told that they do exist.” I lived for two years in Argentina (admittedly 30 years ago) including one year in Gaiman. I must have met hundreds of native Welsh speakers. How on earth did you manage to fail to meet one? They can’t all have died.

LikeLike

That’s interesting to hear. I only spent a day in Gaiman and that was the place where i did find people with some Welsh, but all said it was what they learned in school and none were using at their first language. That included people working in the Welsh tea rooms. They made a fuss of me there when they realised i live in Wales, as they see very few Welsh visitors; most of their clientele are Spanish speaking Argentinian tourists it seems.

I spent most time in Trelew and encountered plenty of people in the museums and restaurants proud of the Welsh heritage (it was amazing how many claimed to be descended from the original Welsh settlers) but none spoke fluent Welsh. They were mostly adults under the age of 40 yrs old, so I supect fluent Welsh may well be more common in the older generation. A lot can change in 30 years!

LikeLike

The museum in Gaiman is run by Fabio Trevor Gonzales to this day. He is fluent. I am still in touch with three families with teenage, 20s children, all raised bilingually, all resident in the village. I lived on the square, J.C. Evans, the street leading down to it, M.D. Jones, had about 80% Welsh-speaking. Also, these days, there is an ysgol feithrin and a bilingual primary school there. All the teachers would be Welsh-speakers. I learned a lot of Castellano when I was there, but socialized overwhelmingly in Welsh. Glad you had a good time.

LikeLike

Thanks again for that insight, Robert. I didn’t find the Museum in Gaiman. I specifically asked the young woman (maybe 30 y.o.) in the Welsh People’s Museum in Trelew if she spoke Welsh. She didn’t; nor did she speak English (we communicated via my poor Spanish and Google Translate). I had a long converstaion with a younger woman in the (excellent) Paleontolgy Museum in Trelew who spoke excellent English. She claimed her great-great grandmother had been on the Mimosa. She had learned Welsh in primary school and sounds like it was an option in secondary school, but she chose to focus on English as she wanted to work in tourism. I asked if Welsh would not have been useful in a area where tourism is connected to the Welsh heritage, but she suggested that she didn’t see her long term future to be in this area and that English is the ‘world language’ as she put it. I also had a young woman working on the till in a supermarket in Rawson who, recognising my Welsh football shirt, wanted to practice a bit of Welsh on me, which was a bit embarrassing given the paucity of my Welsh! So it seems a pretty mixed picture overall.

LikeLike