I had the pleasure of attending a talk by Brian Klaas at the Humanist UK Convention in Cardiff in 2024, so when his new book, Fluke: chance, chaos, and why everything we do matters, came out a few months ago, I got a copy and have just started reading it. Within a few pages I am inspired to write this blog.

He opens with a story I first came across when I visited Japan in 2003. The story starts in October 1926 (a month before my father was born) when Mr H.L. Stimson, a lawyer from New York, took his wife on a romantic vacation to Japan, where they fell in love with Kyoto’s pristine gardens, magnificent historic temples, and rich heritage, just as I did.

Fast forward nnnnnineteen [sic] years and Stimson, a lifelong Republican, had become Secretary of War under Franklin D. Roosevelt, and then under Harry S. Truman when FDR died in April 1945.

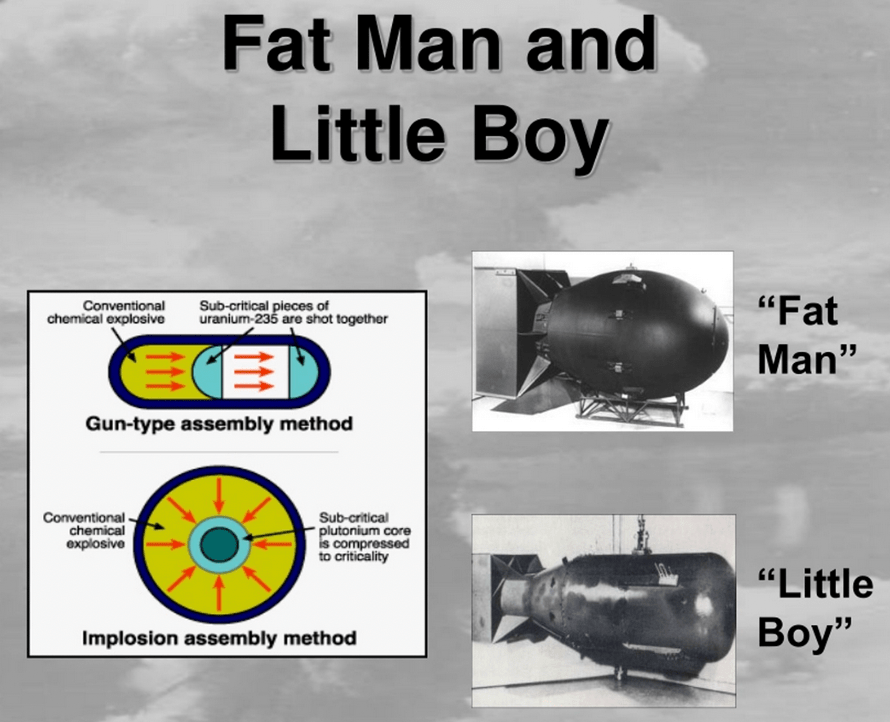

Four weeks after FDR died saw the Nazis surrender and the end of the war in Europe. The focus now shifted to the Pacific and the pressure was on to bring the war of attrition there to an end. An opportunity was glimpsed to bring the Japanese to their knees by deploying ‘The Gadget’ that scientists and the military had been working on in a remote outpost in the deserts of New Mexico.

Despite no successful testing having taken placed, it was concluded that they might as well determine which of the two prototypes is most effective by dropping one of each Japan. The Target Committee therefore needed to come up with the two target cities. Kyoto came out as by far the militarists’ number one target as it was the home of Japan’s most modern warplane factories, was an intellectual centre at the forefront of pioneering technology and a cultural centre and former capital city. The second target was to be Kokura, housing the country’s largest military arsenal. The reserve targets were Yokohama and Hiroshima.

This list of four targets was passed from the Target Committee to Truman’s cabinet for ratification, at which point War Secretary Stimson vetoed the bombing of Kyoto altogether. After much toing and froing, it was agreed that Hiroshima would replace Kyoto as target number 1, while Kokura remained target number 2, with Nagasaki creeping onto the reserve list alongside Yokohama.

And so, on August 6, 1945, Little Boy fell from the Enola Gay, not on Kyoto, but on Hiroshima, killing 140,000 people, mostly civilians going about their daily lives. Meanwhile the civilians of Kyoto escaped this fate because Stimson had had a lovely time there 19 years previous.

Three days later, on August 9, Bockscar dropped Fat Man, not on Kokura, but on Nagasaki because of unexpected cloud cover in the area that did not quite extend as far as Nagasaki. Such small details determined which 80,000 ordinary Japanese folk died that day. Those clouds saved Kokura’s residents and condemned those of Nagasaki to death. To this day, the Japanese refer to “Kokura’s luck” whenever someone unknowingly escapes a disaster.

Of course, although minor details and chance events influenced which city’s populations would be annihilated, the decision to use these weapons of mass destruction at all was the culmination of a near-infinite array of arbitrary factors that lead to the rise of Emperor Hirohito, the education of Einstein, the creation of uranium by geological processes millions of years ago, etcetera, etcetera.

My mother and father would never have met, and I would therefore not exist and be writing this blog piece today, were it not for Hitler and the Nazis invading Poland in 1939; whisking a 14 year boy into forced labour in 1941; sparing his life probably just because he was so young; and him being picked up in the nick of time by the allies in 1944 who fed him back through the lines until he ended up in a hospital in Glasgow come VE Day in 1945. Without then being sold a scam ticket back home in 1948, he would never have ended up in Kent and ending up meeting a Yorkshire lass (with her own unlikely story) in Gravesend.

Whenever we explore anybody’s personal and family histories, we are likely to find numerous examples of Kokura’s luck. We all owe an inordinate amount to luck in ever being born at all, let alone to all the good (and bad fortune) in our lives.

Klaas puts it like this:

“When we consider the what-if moments, it’s obvious that arbitrary, tiny changes and seemingly random, happenstance events can divert our career paths, re-arrange our relationships, and transform how we see the world. To explain how we came to be who we are, we recognise pivot points that were often out of our control. But what we ignore are the invisible pivots, the moments that we will never realise were consequential, the near misses and near hits that are unknown to us because we have never seen, and will never see, our alternative possible lives.”

Tim Minchin puts it like this:

Klaas goes on to make the following logical and pretty darn obvious point, that really got me sitting up and taking notice:

“There’s a strange disconnect in how we think about the past compared to our present. When we imagine being able to travel back in time, the warning is the same: make sure you don’t touch anything. A microscopic change to the past could fundamentally alter the world. You could even accidentally delete yourself from the future. But when it comes to the present, we never think like that…. Few panic about an irrevocably changed future after missing the bus. Instead, we imagine the little stuff doesn’t matter much because everything just gets washed out in the end. But if every detail of the past created our present, then every moment of our present is creating our future too.”

That’s a pretty sobering thought, isn’t it? I don’t think Klaas is suggesting we should get paranoid about the implications of every moment of the day (that way madness surely lies) but it does mean that much smaller things than we can imagine can have significant consequences and following this line of thinking through it means that the deliberate actions we take almost certainly will have knock-on consequences way beyond what we imagine they do. That is a very encouraging thought, isn’t it? Especially for activists that hope to change the world but struggle to see the impacts they are making in perhaps a wider perspective or longer term than we look for.

In 2011, in the conclusions chapter of my book ‘The Asylum of the Universe’, I wrote:

“I am backing myself to be of a rare generation that suffers no major calamity in my lifetime. I hope to avoid direct involvement in war; to avoid being forcibly relocated; to avoid having to source my own food and collect my own water; and to avoid witnessing the breakdown of society around me. I have a sporting chance, I reckon.”

The odds have lengthened considerably in the intervening years. In this time, we have seen multiple genocides, such as in Myanmar, Sudan, Syria, Central Africa and, of course, Palestine. We have seen negligible progress in averting climate catastrophe. We have seen war in Europe. We have seen a groundswell of right-wing populism around the world with fascism raising its ugly head again in Europe and other continents, including in the USA. And Putin has his hand hovering over the big red button. Sadly, technology has moved on such that the frequent cloud over South Wales cannot save us this time.

Is ‘Kokura’s luck’ running out for all of us?